Currently reading

The Lonely Sea: Collected Short Stories

Her Benny

Vedere din Parfumerie

Mysticism and Logic (Western Philosophy)

The Analects of Confucious

Pragmatism: A New Name for Some Old Ways of Thinking

Does Anything Eat Wasps?: And 101 Other Unsettling, Witty Answers to Questions You Never Thought You Wanted to Ask

Mutual Aid

City of Djinns: A Year in Delhi

The Brothers Karamazov

Captain Corelli's Mandolin

Never going to read this or anything else by the same author. His politics are very likely foul. DNF

Never going to read this or anything else by the same author. His politics are very likely foul. DNF

The Celestine Prophecy

If I'd ever smoked, I'd say this had the potency and the smell of skunk. Amazed it didn't emit a magical, foul miasma, not only because it was flammable plastic, but it seems, according to another top review, that Redfield was advocating for a payment-for-energy exchange, through mail-order forms at the back of some books.

If I'd ever smoked, I'd say this had the potency and the smell of skunk. Amazed it didn't emit a magical, foul miasma, not only because it was flammable plastic, but it seems, according to another top review, that Redfield was advocating for a payment-for-energy exchange, through mail-order forms at the back of some books.

The Story of Medicine: From Bloodletting to Biotechnology

If I remember correctly, Ms. Dobson is/was an editor or professor of medical history at Cambridge or somewhere similar. But this work reads more like a magazine at the doctor's office, a comforting survey of treatments, without the details or messy analysis. Although, as magazine articles, the human interest stories would seem pretty thin.

If I remember correctly, Ms. Dobson is/was an editor or professor of medical history at Cambridge or somewhere similar. But this work reads more like a magazine at the doctor's office, a comforting survey of treatments, without the details or messy analysis. Although, as magazine articles, the human interest stories would seem pretty thin.So I naturally learned a shard or two of history on subjects a century old or more, mostly regarding famous studies that demonstrated the cause of cholera or found a (mostly ineffective) vaccine for TB. Many such seminal studies were ignored for decades after their discovery, says the book (in one sentence, usually). It's strange and unfortunate that this writer makes no attempt to offer explanations for such regrettable and deadly missed opportunities.

The crushing weight of tradition may have begun with one famous medical text from Greece, translated into Arabic and so on, which, among other things, made balance of the four humours so emphatic for 1000 years or so. I find it interesting that the humours described are so emphatic and so balanced at the same time, as so often seems baffling and compelling in Greek conversation, at least in English. You'll still find people who think positive thinking cures cancer. Did we get that from the Greeks or from the Asians who emphasized emotional balance far earlier in history?

Per its academic or British origins, the book contains a few recommendations towards the back of the book regarding regulation of future trials and studies. They are short, bullet-pointed vagaries, as described and administered by official, probably remote institutions. Whether this approach was missing in recent history or was itself the cause of missed opportunities, as medical breakthroughs became temporarily lost, is not discussed or made clear in the book.

Water for Elephants

Tried 15 more pages, got worse, with manic, process-obsessed naive old men incapable of making human connections. The David Letterman of literature. DNF

Tried 15 more pages, got worse, with manic, process-obsessed naive old men incapable of making human connections. The David Letterman of literature. DNF

Dibs in Search of Self

An easy and honest read, nice to see that Dibs became a full human being with some unselfish and perceptive help, but not sure the solution, per my update, is especially recommended for other troubled children, possibly Dibs included.

An easy and honest read, nice to see that Dibs became a full human being with some unselfish and perceptive help, but not sure the solution, per my update, is especially recommended for other troubled children, possibly Dibs included.

Shouting At The Telly

There really should be a program to rehabilitate good book titles as entirely better books. I'd thought I'd hit a kind of disturbing, time-saving luck by plucking an essay from the middle of the book, a short essay showing what a deprived, Telly zombified boor the editor was, but no, the intellectual depravation runs at random throughout the book. The topics are exclusively random television programs from England as well. Accident? Per the title: "Hey Brits, stop charging me 6 euro to hear you spew junk!" At least real Telly overseas is "free" in some way.

There really should be a program to rehabilitate good book titles as entirely better books. I'd thought I'd hit a kind of disturbing, time-saving luck by plucking an essay from the middle of the book, a short essay showing what a deprived, Telly zombified boor the editor was, but no, the intellectual depravation runs at random throughout the book. The topics are exclusively random television programs from England as well. Accident? Per the title: "Hey Brits, stop charging me 6 euro to hear you spew junk!" At least real Telly overseas is "free" in some way.

The White Tiger

It's difficult to overstate the relief I felt, reading this fable after spending Romanian winter with heady, badly printed encyclopedias. It feels as if I've known more than a few White Tigers in my life and would even consider myself a form of one. Not that I, a Westerner, or possibly even most Indians, have ever experienced hardships quite so strident as "The Darkness". My experience has been Western and therefore a random, pointless sort of backbiting, which this Indian "White Tiger" can only aspire to himself, by obliterating family, caste, and social conventions from The Darkness. To this Western reader -- and that is the writer's intended audience -- The Darkness seems like a convivial place by comparison to any Western suburb stuffed with would-be White Tigers, and that is also the author's intent. Like the White Tiger, we Western Tigers are inured to every suffering save self-centred economic suffering, and we have slowly convinced ourselves that socially-induced fear, not ignorance, is holding us back from success.

It's difficult to overstate the relief I felt, reading this fable after spending Romanian winter with heady, badly printed encyclopedias. It feels as if I've known more than a few White Tigers in my life and would even consider myself a form of one. Not that I, a Westerner, or possibly even most Indians, have ever experienced hardships quite so strident as "The Darkness". My experience has been Western and therefore a random, pointless sort of backbiting, which this Indian "White Tiger" can only aspire to himself, by obliterating family, caste, and social conventions from The Darkness. To this Western reader -- and that is the writer's intended audience -- The Darkness seems like a convivial place by comparison to any Western suburb stuffed with would-be White Tigers, and that is also the author's intent. Like the White Tiger, we Western Tigers are inured to every suffering save self-centred economic suffering, and we have slowly convinced ourselves that socially-induced fear, not ignorance, is holding us back from success.Like any comforting fable for children or foreigners, "The White Tiger" is telling a highly simplified tale, as told by a wise fool, using a few recognizable symbols and totems. But it is a balancing act between ridiculing Indian corruption and exposing Western buggery, a blend of condescension and mock irony which, thankfully, managed to convince an audience of English judges at Man Booker.

It's highly likely that less than glowing Goodreads ratings reflect opinions of actual Indians readers, who naturally have a deeper knowledge of India's cultures and politics. What part of Indian culture escapes Mr. Adiga's journalistic contempt by story's end? Like a kind of satire, "The White Tiger" is ultimately taking a conservative tack, ridiculing any political or social calculations which undermine caste and family. Hence his running commentary from the narrator and auxiliary characters against modern conventions such as parliamentary democracy, which turn castes of sweet makers into brutal social climbers and reward any monkey with money for political bribes. Is parliamentary democracy also the reason the White Tiger is so confident he'll easily bribe policemen who spend their day in front of Gandhi's portrait?

For all the scheming behind his mighty name, where did the White Tiger end up, per the book's theme? A minor entrepreneur, bragging about his success to some diplomat from China, writing a letter no one will read. As he bragged again about the chandeliers in his home, I was reminded of news accounts of an American man who killed his family, then burned down his house, somehow believing that this would help escape some debt. The story goes that the chandelier found in his house would have paid off his debts in full.

Overall, I really enjoyed a simple morality tale. It didn't teach me anything I didn't know, and it was likely too simple for a sophisticated Indian reader. It may even be a much improved retelling of magazine detective stories mentioned in the book. So I can't say it earned its status as one of the top 5 Indian works of all time (says one list), but it would make an excellent movie, in the style of American Psycho.

The White Tiger

It's difficult to overstate the relief I felt, reading this fable after spending Romanian winter with heady, badly printed encyclopedias. It feels as if I've known more than a few White Tigers in my life and would even consider myself a form of one. Not that I, a Westerner, or possibly even most Indians, have ever experienced hardships quite so strident as "The Darkness". My experience has been Western and therefore a random, pointless sort of backbiting, which this Indian "White Tiger" can only aspire to himself, by obliterating family, caste, and social conventions from The Darkness. To this Western reader -- and that is the writer's intended audience -- The Darkness seems like a convivial place by comparison to any Western suburb stuffed with would-be White Tigers, and that is also the author's intent. Like the White Tiger, we Western Tigers are inured to every suffering save self-centred economic suffering, and we have slowly convinced ourselves that socially-induced fear, not ignorance, is holding us back from success.

It's difficult to overstate the relief I felt, reading this fable after spending Romanian winter with heady, badly printed encyclopedias. It feels as if I've known more than a few White Tigers in my life and would even consider myself a form of one. Not that I, a Westerner, or possibly even most Indians, have ever experienced hardships quite so strident as "The Darkness". My experience has been Western and therefore a random, pointless sort of backbiting, which this Indian "White Tiger" can only aspire to himself, by obliterating family, caste, and social conventions from The Darkness. To this Western reader -- and that is the writer's intended audience -- The Darkness seems like a convivial place by comparison to any Western suburb stuffed with would-be White Tigers, and that is also the author's intent. Like the White Tiger, we Western Tigers are inured to every suffering save self-centred economic suffering, and we have slowly convinced ourselves that socially-induced fear, not ignorance, is holding us back from success.Like any comforting fable for children or foreigners, "The White Tiger" is telling a highly simplified tale, as told by a wise fool, using a few recognizable symbols and totems. But it is a balancing act between ridiculing Indian corruption and exposing Western buggery, a blend of condescension and mock irony which, thankfully, managed to convince an audience of English judges at Man Booker.

It's highly likely that less than glowing Goodreads ratings reflect opinions of actual Indians readers, who naturally have a deeper knowledge of India's cultures and politics. What part of Indian culture escapes Mr. Adiga's journalistic contempt by story's end? Like a kind of satire, "The White Tiger" is ultimately taking a conservative tack, ridiculing any political or social calculations which undermine caste and family. Hence his running commentary from the narrator and auxiliary characters against modern conventions such as parliamentary democracy, which turn castes of sweet makers into brutal social climbers and reward any monkey with money for political bribes. Is parliamentary democracy also the reason the White Tiger is so confident he'll easily bribe policemen who spend their day in front of Gandhi's portrait?

For all the scheming behind his mighty name, where did the White Tiger end up, per the book's theme? A minor entrepreneur, bragging about his success to some diplomat from China, writing a letter no one will read. As he bragged again about the chandeliers in his home, I was reminded of news accounts of an American man who killed his family, then burned down his house, somehow believing that this would help escape some debt. The story goes that the chandelier found in his house would have paid off his debts in full.

Overall, I really enjoyed a simple morality tale. It didn't teach me anything I didn't know, and it was likely too simple for a sophisticated Indian reader. It may even be a much improved retelling of magazine detective stories mentioned in the book. So I can't say it earned its status as one of the top 5 Indian works of all time (says one list), but it would make an excellent movie, in the style of American Psycho.

The Dybbuk and Other Writings by S. Ansky

It was eerie to read that this man ran the Yiddish center in Vilnius before WWII nearly wiped out the Yiddish population. There's every possibility that some kind of cousin, but not my great-grandparents, were involved in one side or the other of that conflict.

It was eerie to read that this man ran the Yiddish center in Vilnius before WWII nearly wiped out the Yiddish population. There's every possibility that some kind of cousin, but not my great-grandparents, were involved in one side or the other of that conflict.This collection is probably rare in some way, since it includes other, less famous, translated writings by Ansky, which may never see the light of day in another forum. His one piece about a Christian woman in Russia who registered herself as Jewish, then refused on principle to change her name back to a Christian one, which would have safeguarded her from constant persecution by authorities, was quite touching.

Unfortunately, the text of the Dybbuk play was struck out in places with heavy pencil. It opens with reference to Yiddish religious songs being sung and all in all would seem to benefit better from a performance than an unsophisticated reading.

Strange to say for such a famous Yiddish play, the old movie shot in Poland's Jewish ghettos before the Nazis got there has no English subtitles translating the Yiddish, at least on Youtube. Something to look out for...

Love Poems

Bought this because I was surprised to find how few love poems are rated as popular on internet poetry sites, at least in English. I wouldn't have included Katherine Mansfield. Or possibly Emily Dickinson. Thomas Hardy mumbled impracations into the same sleeve where he jotted down latin derivations of topology. And I was going to complain about Rupert Brooke, but the poor man was conspired against in affairs with women, by men who wrote poems to his "boyish good looks." Where is Pushkin, the most famous (love) poem in Russian, even if it doesn't translate well?

Bought this because I was surprised to find how few love poems are rated as popular on internet poetry sites, at least in English. I wouldn't have included Katherine Mansfield. Or possibly Emily Dickinson. Thomas Hardy mumbled impracations into the same sleeve where he jotted down latin derivations of topology. And I was going to complain about Rupert Brooke, but the poor man was conspired against in affairs with women, by men who wrote poems to his "boyish good looks." Where is Pushkin, the most famous (love) poem in Russian, even if it doesn't translate well?The ending credits also confirm that most of the overwhelming illustrations come, almost without exception, from the romantic era, so that everyone seems so alert with confused longing that their aura has crimsoned the background. The best part? The editorial choice on dividing the poems, although the poems never quite fit their label of course:

Nascent Love, Celebration and Devotion, Fulfilled Love, Departed Love, Beware Love, Lost Love and Remembrance

Illustrated Encyclopedia of Signs and Symbols: Identification, Analysis and Interpretation of the Visual Codes and the Subconscious Language that Shapes ... and Emotions (Illustrated Encyclopedias)

I strongly admire the effort, I really do. But the fact that I learned so much from these concise chapters about every world religion and symbol system says more about me than it does, possibly, about the book. I really thought I'd hit the jackpot when the book offered a single explanation for the symbolism of the triple spirals at Newgrange. Those spirals are everywhere in Europe and they always have a different explanation. The exhibit at Newgrange suggested that their interpretation is very much up for debate, but this book and its primary author with an Irish surname, gives just the single answer: the Celtic triple goddess: a woman in the three primary stages of life.

I strongly admire the effort, I really do. But the fact that I learned so much from these concise chapters about every world religion and symbol system says more about me than it does, possibly, about the book. I really thought I'd hit the jackpot when the book offered a single explanation for the symbolism of the triple spirals at Newgrange. Those spirals are everywhere in Europe and they always have a different explanation. The exhibit at Newgrange suggested that their interpretation is very much up for debate, but this book and its primary author with an Irish surname, gives just the single answer: the Celtic triple goddess: a woman in the three primary stages of life.At some point I began to wonder just who would go to the effort of synthesizing every symbol system of mankind, without apparently editorializing. The answer, it appears, is in the author's profession as a process-orientated psychologist. To be honest, his chapter devoted to that psychology is the most muddled of the bunch, but it seems to be a process of customizing your symbolic life to symbols as you yourself see them, probably with the help of someone like the writer who has many of the better known ones at hand. Men who stand up straighter to be more like the black knight in their own lives, and other hoary descriptions.

This was my first clue that "Hey, I'm reading a book for dummies! And I'm enjoying it." Then we came to Jung, who is described as hearing the voice of a wise inner figure called Philemon and "in his latter years spent a great deal of time....playing in the sand." Even if I get hints that the primary writer is not a Jungian, it sounds as if all of Jung's eggs cracked in the same bag.

And it appears the author borrowed that bag, taking Jung's idea of synchronicity and turning into a fairy all-connected world, increasingly demonstrated by "quantum physics and process-oriented psychological developments." If you're wary to let all those birds into your brain at once, the chapter ends with a photo of a single leaf, falling, catching the light, flirting for your attention, in some synchronicity definition of "flirt."

The catalog of symbols at the end is fascinating. Who knew there were so many versions of the swastika? Who knew that a banana is Freud's penis and nothing more?

Insight Guides Athens (Insight City Guides)

It's a pity that informative guidebooks aren't the ones best suited to travel. But I bought this for 2 euro at a remainders shop, having felt guilty that I'd spent so much time in Greek Macedonia without having seen Athens. I'd had the impression that I hadn't seen the "real" Greece. Let's forget that Mt. Olympus is in Macedonia, that Alexander the Great turned Greece into a world empire from his home in Macedonia, and that Paul built some of his first Christian churches in the region, if we're talking about Christian influence on modern Greeks.

It's a pity that informative guidebooks aren't the ones best suited to travel. But I bought this for 2 euro at a remainders shop, having felt guilty that I'd spent so much time in Greek Macedonia without having seen Athens. I'd had the impression that I hadn't seen the "real" Greece. Let's forget that Mt. Olympus is in Macedonia, that Alexander the Great turned Greece into a world empire from his home in Macedonia, and that Paul built some of his first Christian churches in the region, if we're talking about Christian influence on modern Greeks.Nor is Athens the absolute core of Greek history, judging by its fluctuations in good fortune. It may only be haphazard Continental classicism which kept Athens alive as a city at all.

This exceedingly strange and informative guide from 1995 is laid out much like a textbook and attempts to condense Greek history and culture into approximately 30 pages. It makes me feel marginally better about skipping Athens, since the British editors bang on, time and again, about their unwillingness to review a city so difficult to love, starting with the very first paragraph of the book. A team of British writers and photographers then itemize the caustic, noisy, polluted, architecturally vapid knocks against the place. It is largely a single chapter about modern Greek culture, written by a half-Greek contributor, which alerted me to a level of condensed and vital detail I'd been missing with a more theoretical survey of Greece I'd been reading just before this.

Athens is described as the noisiest city in Europe, with rude people criss-crossing your path, laden with cardboard boxes. This is not the modern Macedonia I saw, where music and sound don't seem to exist, unless it's the buses or one of the many hidden squares with live music. But modern Athens, even more so than modern Macedonia it seems, is mostly a new city of immigrants from Asia Minor. After the Romans left Athens, the city became so insignificant, that one of the French Crusaders became its sole owner, gave it to his son, who lost it to a few Catalan mercenaries whom he owed debts. In what seems to be an ongoing habit, minor European royalty then took it over. That seems to account for 500 years without notable status, made worse by an ill-fated rebellion against the Turks which utterly destroyed and emptied out the city in the 1800s. The number of Athenian citizens by then numbered in the 1000s. It was in fact Europeans who were the ones to insist on making Athens a capital again, and Athens eventually filled in with new citizens, as later politics drove millions of nominal Greeks from Asia Minor, to Athens and Macedonia. Since these new citizens had been living in what is today, Turkey, one wonders if the character of "the artful dodger" under Ottoman dictatorship, as described in the chapter about modern Greeks, has stronger origins in Asia Minor. Not much, apparently, could be done about the urban landscape laid out by German engineers, or the mostly modern buildings built after that anti-Ottoman rebellion destroyed older architecture. It didn't help that "Venetian artillery blew a large part of the Parthenon sky-high."

Lawrence Durrell, who has little to say in praise of the Cyprus landscape, states in one sentence that "Athens was beautiful as usual." Although he was sitting under the Acropolis, I have to wonder if these British guidebook writers made a hash of it. I would like to think that the book is most valuable as a history primer, but here again, I have to wonder at claims that Greeks have the first recorded cookbook and first historical description of some kind of school in the world. The fact that they think British Museums are protecting the "Elgin Marbles" from the Greeks is also suspicious. Here, at any rate, are the interesting historical asides, so that neither you nor I have to carry the book anymore:

-- Athens copied the culture of ancient Crete, which took metal work and culture from the East

-- The Greek Classical Age lasted just 150 years

-- "Real" Athenians were short, dark Ionian sailors, with a reputation for "shrewdness", who eventually fled to Asia Minor

-- Many Athenians and Greeks moved on to Alexandria or Constantinople.

-- Ancient Athens restricted citizenship too much to be called a democracy

-- Pot shards (ostraka) used for voting show that a certain amount of ballot stuffing went on.

-- After Athens beat back a Persian invasion, it collected a defence fund from surrounding city-states and used the money to build monuments to itself.

-- On many occassions, people trapped in the Acropolis surrendered, only to be slaughtered

-- Right to hide within the walls of the Acropolis were the origins of Greek citizenship.

-- Turks storing gunpowder in Propylaia were blown sky high by a lightning strike.

-- The symbolic prizes at the Olympics: first prize "a blameless, accomplished woman", second "a clever woman"

-- Dionysian feasts had musical contests between choirs dressing and acting like goats.

-- The games were abolished in AD 394 by a Byzantine emperor, partly because he objected to the nudity.

-- Homer may have never seen Athens

-- Byron died without heroism, after having been caught in a rain storm

-- Many Greeks have the first name "Byron"

-- Greeks with ancient names or names like "Byron" have no Name Days.

-- Greeks describe their fear of responsibility as "efthinophobia."

-- In Greece until 1995 "the leader is king".

-- It is common to blame political problems on a history of "ksenos daktylos (foreign finger)"

Brazzaville Beach

Here's where I'll probably stop, page 244.

Here's where I'll probably stop, page 244.Finding this book was a marvelous and strange coincidence. It was one of two or three English books from a lonely, hodgepodge street seller at a quite remote metro stop in Sofia, Bulgaria. It's lucky and strange that I found this fictional reminder that alleged chimpanzee pacifity in [b:The Naked Ape: A Zoologist's Study of the Human Animal|33297|The Naked Ape A Zoologist's Study of the Human Animal|Desmond Morris|https://d.gr-assets.com/books/1324595064s/33297.jpg|1374011] -- another Bulgarian treasure -- is badly misinformed.

It seems as if William Boyd would do very well to write nonfiction or science. Here on GR, I have added an excellent, concise quote from the book about losing track of time and its neurologic basis. Boyd's writing style might be described by the preface to a collection of ancient Celtic writings I've browsed. The professor who collected and translated those writings points out that, far from being the sort of magical realism attributed to Celts at a certain point in history, most of the writing is in fact coldly realistic.

The realism just gets tedious when Boyd spends pages describing the geometry of every tree and cliff in Africa. He appears to believe that the descriptions of chimps killing each other will add the necessary element of disbelief. But it is in fact the pointless intrigues by the main character's scientific colleagues and herself which beggar belief.

Oddly enough, the dispassionate indexing of details begins to feel soothing and indicative of mutual concern if it's used to describe subtleties during a family dinner. Here, Boyd pulls the almost impossible feat of making dull middle class life sound more interesting than even Anne Tyler writes it. I'm half expecting to finish the book anyway, just to read another becalming dinner scene.

What the book is probably attempting to do, with a combination of little and no subtlety, is contrast chimpanzee aggression with that of the researchers themselves. Perhaps the two threads will blend better toward the end. This book may have helped my thinking, in that I'm less inclined to believe that chimp habits are trainable, but that accepting we are little more than chimps certainly can't reduce aggression.

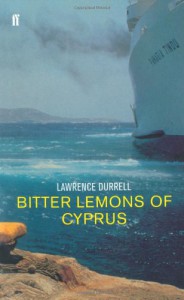

Bitter Lemons of Cyprus

I bought this because I enjoyed his little brother's account of life in Greece very much. I was also hoping to learn more about Greek influence and Cyprus as a tourist destination.

I bought this because I enjoyed his little brother's account of life in Greece very much. I was also hoping to learn more about Greek influence and Cyprus as a tourist destination.Although the first paragraphs of the book are quite purple, it seemed to promise to deliver the goods on stereotyping Cypriot Greeks, if only, it turns out, because Lawrence Durrell is so British.

I have a tiny, short tourist guidebook for Cyprus which happens to dismiss this book in one sentence. I thought that would be enough, but given the praise and high average ratings here, more needs to be said.

His early chapter about buying a house in Cyprus is easily one of the funniest things I've ever read. It was only in the hours after reading it that I had to reflect that, hang on, this guy sounds like a real jerk.

He arrives having already lived in Greece and speaking Greek. He says he didn't move to Athens instead because of the costs. He makes appeals directly to Greeks to honour their tradition of hospitality, then he hires a Turkish man (whom he describes as a reptile) to dissemble and shout at Greeks until they sell him a home with some magical balcony for practically nothing.

Then, in keeping with brief references in his little brother's book, he picks a high point in his house to slowly eat grapes and crack the whip on Greek workmen who may be lingering to tell the stories he loves so much.

But that is only a tiny hint of what's to come.

Although he claims to hate politics, he takes a job as an Information Minister with the British government of Cyprus. True, it appears to have been an inopportune time, with, according to Durrell, Athens radio whipping up the stupid peasants with ideas of independence.

The real position of Lawrence Durrell? "As a conservative, I fully understand, namely; 'If you have an Empire, you just can't give away bits of it as soon as asked.'

He does relay the opinion of one British official that not a single university, swimming pool, or many other amenities had been built in Cyprus under British rule. Then, as a member of the British government himself, Durrell slowly provides a bare sketch of the timeline, as anti-British sentiment builds. It seems a new constitution, with mostly stick and no carrot, was outlined in broadsheets. Durrell can take a breather to add random notes about sunsets in the book, but he can't be bothered to provide details on this constitution, even in an official capacity.

Then, British troops shoot three youths "under severe provocation" in Limassol, a "trivial" incident. No greater detail provided. His greatest recommendation? More police.

And so the rest of the book apparently goes, giving Durrell's unabashedly nationalistic sketch of the war of independence in Cyprus.

Skipping extremely rapidly though the rest, I came on this choice bit:

"Coming out of the Colonial Office, I knew at once that the Empire was all right by the animation of three African dignitaries...They gave off over-powering waves of Chanel Number 5 - as if they hosed themselves down with it...like genial elephants".

Some of his knowledge of Greece doesn't seem without merit, such as the fact that Europeans somehow forget that modern Greece's greatest historical influence is probably the Byzantine era. Or his confirmation that a few "lunatics" in Crete or Rhodes could start a struggle for Greek independence almost anywhere.

Would it be fair to say that Durrell is just a product of his time? I also have another book written by his little brother, this time in Argentina. Not only is it very funny, but it is remarkably unselfish, with heart. Gerald makes a short appearance in this book, and although not much is described, he wins more Greek favour in a few days than Lawrence deserved with his dissimilations, lies, and empire building.